At the Ends of the Earth

Death Valley National Park, CA - Late April, 2012

Excitement is a hell of a drug.We woke early again, and despite enjoying little sleep, I felt no lassitude -- I was ready to get back out there. Alice and French whipped up another breakfast, involving home fries, eggs, toast and avocado, before we got in the car. Unlike the day before, our car was fully packed with two days' worth of gear: Tents, packs, camp stove, chairs, a cooler brimming with food and beer, etc. It wasn't yet 10 am and we were already blasting down dusty desert roads, my ears popping as we crept lower and lower below sea level. The road stretched straight and open before us, my stomach jumping as we lurched forward. Soon, the sagebrush and other scraggly plants disappeared and the landscape was rendered Martian, with rocks and sand defining the ancient lake bed. In the distance, mountains loomed, hidden by heat and blowing sand.

|

| Entering Desolation Canyon |

Eventually, we pulled up to a well-worn, dirt cul-de-sac and got out of the car, bringing only water with us. The nearby hills were made up of hard, bulbous rock flanked by packed sand, ribbed and eroded by what little water fell from the sky. The mountains were striped red and black by some mineral deposits. Everything was very still, quiet, hot. I followed Alice and French up a winding path into a ravine in the mountainside. This was Desolation Canyon (where they filmed part of

Star Wars, which was why they took me here -- I love

Star Wars, like, a whole bunch).

|

| Mountains above Desolation Canyon |

Desolation Canyon was wider than Grotto. It's ground was a dried, packed sand, where Grotto's was loose and beachy. Little channels bled blue and black down the banks of the mountains. We were exposed to the sun and there was naught a place to find shelter, not even a bush to sit near. Walking deeper into the canyon, the mountains above us became a mosaic of different colors: Burnt orange, red, black and tan, with ribbons of white creeping down. The sky above was cloudless and singeing. Life there was muted and the canyon felt abandoned and forlorn (one might say "desolate"). Still. The only noise I heard was the occasional tumble of small rocks down the canyon walls (a lurking Jawa perhaps?).

Leaving Desolation Canyon, we traveled deeper into the park to the lowest point in North America -- Badwater Basin. At the bottom of the valley, the basin is a large playa -- a dried lake bed -- covered in caked salt. The nearby mountains to the east -- which eventually extend to Funeral Peak -- are jagged, broken, rough and dark. High up on the mountainside is a large sign that reads "SEA LEVEL," 282 feet up. A boardwalk extends out from the parking lot, over saline pools and onto the salt flat. The rumble and roar of passing motorcycles clashed with the mountains before dissipating over the endless valley. Peering into the pools, where salt crystallized and formed little spires, small organisms darted about. Some sort of orange-brown bacteria blanketed the bottom of the pool like a rusty moss. In the distance, we could see Telescope Peak, the tallest mountain in the park. Where the boardwalk ended, the crumbling salt was packed down by foot traffic. Unknown vandals named "Shannon" and "Matt" had let all park visitors know they had been there by carving their names in the salt -- a marking that would take decades to wash away (maybe Matt and Shannon will come back by then to remind us, once again, that they were here). Droves of people walked out of their cars and onto the flat to experience America's lowest point (geologically, that is) before getting back into their vehicles to drive somewhere else in California. Maybe somewhere with trees. The American Dream.

* * * *

|

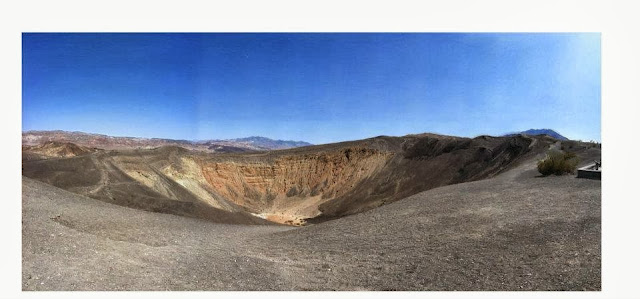

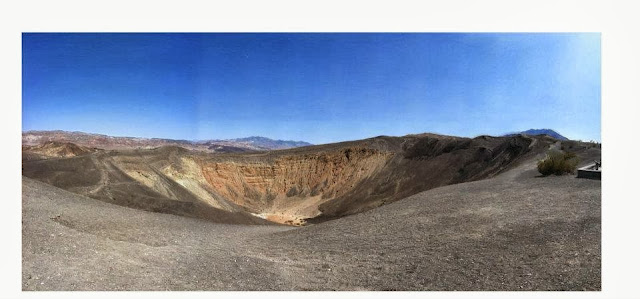

| Ubehebe Crater |

We, too, returned to the car and made our way north, taking a detour down a winding road, shrouded by steep walls of rocks and imposing hills, to a breathtaking scene: Artists Palette. It is a richly colored mountainside, boasting the most extreme range of colors I've seen in nature. Deep blue to turquoise to peach to red to chocolate to ivory. On and on, titillating the imagination and pushing the notion of the color wheel. We viewed the scene for a while before moving much further north to Ubehebe Crater, a dinosaur of a volcano. Dormant, dark and desolate. The land rolled and bounded away from us, pocked and ashen from the last eruption -- over 2,000 years ago.* Ubehebe is Timbisha for "big basket in the rock."

|

| Joshua tree with seeds. French was very excited. |

Leaving the road to Ubehebe, we headed south west and away from Death Valley, passing a ranger station -- the last building for 90 miles, by the crow. It was a desolate, remote part of the park. The land sloped up away from the road, dotted with stunted Joshua trees. The mountains beyond were marked by diagonal colored stripes and pinyon pines, providing cover for bighorn and mountain lions alike -- open wilderness.

|

| Climbing the monadnock in Racetrack |

We passed no cars and, eventually, left the paved road altogether, signifying our arrival in Racetrack Valley. The road was graded to prevent washouts, making it appear like it had been driven on by a tank, giving us a bumpy ride. It was fun for the first few miles, but after an hour, the novelty had worn off. Alice taught me how to spot old survey mine entrances -- bleached white mounds on the side of the mountain -- and we got quite good at spotting them along the slow drive. When we got to the bottom of the playa, we pulled into a parking lot next to a vacant Winnebago. It was still hot, but a pleasant breeze from the south made it enjoyable to walk about. The ground was cracked into strange geometric shapes, where water had escaped the sun by draining beneath the clay. Out on the flat stood a monadnock. We made for it and spent some time climbing over the bulbous brown rocks, spotting little lizards lurking in rocky crags. Watching where I put my fingers and toes -- one must be ever-conscious of scorpions and buzzworms -- I made my way to the very top of the rock and looked out on the land. The pan around us was flat (playas are geologically the flattest surface on the planet) and ecru. The mountains beyond were a mix of maroon, gray-blue, white and dusty brown, slopping gently towards the valley floor.

I noticed tire tracks carved into the playa floor, whipping around in donuts, figure-eights, and other winding shapes. Climbing down, I asked Alice and French about the tire tracks. They told me that a few weeks before, shortly after a rain, some asshole -- perhaps the King of the Assholes, or at the very least a duke -- got the inspired idea to drive his truck over the dried lake bed. Because America. Whether or not he was aware that the playa was wet when he drove on it was not known, but what was known was that he had a notion that driving on the playa was illegal -- there are signs everywhere indicating this. Because the pan was still wet when he took his metal steed out to the ancient lake bed, and water has a tough time getting through clay, the surface of the ancient lake bed was mud, allowing his tire tracks to become embedded in the clay for all to enjoy. What's more, the individual didn't do this act in the dead of night, or when no one was around. No, he did it in full view of a host of tourists. One managed to snap a few shots of his license plate and showed them to the park rangers. Before long, every park ranger and park lawman was on the lookout for the gentleman, and it wasn't long before they found him. When he was finally pulled over, the arresting officer was surprised to find that he knew the man, because the perp was a local cop. Perhaps this explained the donuts.

|

| Racetrack Valley from the Homestake Mine |

* * * *

|

| Magic rocks! |

We traveled further south in the valley to the other end of the playa to explore Racetrack Valley's most famous feature. At the end of the lake bed is a hill made up of broken rocks. Occasionally, the rocks roll off the hillside and onto the pan. And, every so often, these rocks move across the valley floor, carving trails as they grow. For a long time, folks thought this was some sort of magic, strange magnetic feature, or alien meddling (many still do, especially the last part. The desert does strange things to people's heads).

The best -- or most reasonable -- theory is that when the playa gets wet, the clay becomes viscous and strong winds can blow the rocks around, creating the trails. When the water evaporates and the clay hardens, the trails stay. No matter what theories are out there, no one has ever seen the rocks move, and no one knows how it really happens. Maybe it is aliens (the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence!).

|

| French walking on the playa |

Splitting up, we followed the mysterious trails as they zigged and zagged across the desert floor. But soon, our stomachs rumbled and we made our way up the road to the Homestake Dry Camp at the southern end of Racetrack Valley. There were a few clearings in the creosote bushes and we picked the one farthest from the main road and the back country toilet (because, well that should be obvious). After we'd set up camp and had a bit to eat, we grabbed a couple beers and made our way down an old road towards the edge of the valley. On the way, I spotted a large, fairly fresh scat on the side of the trail. It had folded in the middle and had a piece of burned toilet paper sticking out of it. Despite the presence of paper, it was certainly not human -- bits of bone and hair stuck out of it. The scat was still dark and malleable (touched it with a stick, I swear), so we knew it was less than a week old. Excited about my new

Scats and Tracks app by Falcon Guides (worth every penny), I looked up the feces and was unsettled by my findings. I showed the suspect to French and Alice and they agreed: Mountain lion. Normally, this would have put me on edge, but we decided there were enough burros and mountain goats to keep a cat happy. Besides, they move far and fast, and this one probably wasn't around anymore.

|

| Old water truck. |

Ahead, we spotted a rusting, yellow water tank trailer sitting atop a hill, riddled with bullet holes and a few bits of graffiti. There was an old foundation nearby and the ground was strewn with rusty cans (archaeologically quite significant, I'm sure!). We perched on the old foundation and viewed the landscape before us. To the east and west, imposing mountains ran the length of the valley. Because this was an ancient lake bed, the valley bowed to the north and the south. The parallel mountain ranges never met, but merely dipped below the flat horizon line, giving us the feeling that the world simply dropped off at the northern and southern ends of Racetrack. Nothing could be seen beyond the distant horizons. We were sitting at the edge of the world, with truly nothing around for miles. The silence was absolute. It is the farthest from anything I've ever been, and the closest to nothing.

|

| Free boots! They didn't fit. |

Shadows stretched from the mountains as we made our way further up the road. Passing over hills, we could see the distant lights of RVs and campers in Saline Valley, twinkling in the early dusk. Ahead, structures jutted out from the mountainside. Sun burned wooden structures and gnarled metal piping of ore chutes and old mines were arranged haphazardly on the bluff, with jackknife trails leading to older mines high up on the mountain -- the Homestake Mine. The place had an eerie vibe to it. It had obviously been long forgotten, but felt as though someone might return at any moment, like being in someone else's house, waiting for them to come home -- must be a condition of living in the city, always expecting more people. Walking toward one open mine, I spotted a derelict pair of cowboy boots on the road, waiting for some forgetful owner to come reclaim them. We peered inside the mine shaft. About five feet in, the way was blocked by horizontal wooden beams. Alice told me that this was to let bats come and go from the abandoned mines and to keep intrepid morons out. (It's almost surprising how many people venture into these old holes, only to never return. Almost surprising.)

|

| Homestake Mine |

It was growing darker and there was catamount shit nearby, so we hightailed it back to the site to enjoy the best camp meal I've ever had. With onions, peppers, kielbasa, Near East rice mix and a couple cans of Bumble Bee canned chipotle chicken (which is absolutely delectable. Side note: Dear Bumble Bee, please sell this in Boston.), they made a scrumptious jambalaya, which I could have eaten ad infinitum.

By the time our dinner was finished, the night was upon us. We sat around and talked, our headlamps providing light (did you know campfires in the desert aren't always a good idea? The more you know). After the bright moon slid below the mountains, we walked two miles down to the Racetrack playa. We took our shoes off and walked across the warm dry clay, letting my hobbit's feet absorb the day's warmth, looking up at the brilliant stars above. Never had I seen such lights, the Milky Way Nebula, any of it. It was brilliant and made me feel like I was spinning, dizzy. French, Alice and I laid down on the tepid ground and watched the stars slowly glide over our endless canopy as I drifted to sleep.

|

| The stars at night are big and bright. |

Continued in Part III

*Evidence shows that the last eruption happened between 1,000 and 2,000 years ago, with some estimates ranging from 7,000 years to as recently as 800 years. So really, no one know -- but it was a while ago.

No comments:

Post a Comment