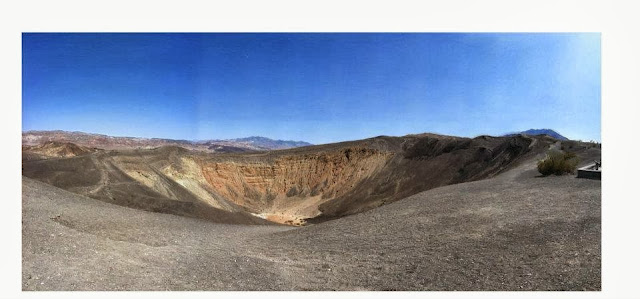

A Study in the Shades of Brown

Death Valley National Park, CA - Late April, 2012

After visiting the American Southwest, there's this feeling I get sometimes that envelopes me. No, it's not Valley Fever. It's this rush of energy I feel inside: My stomach jumps, my arms tingle, and -- but for a moment -- I can feel myself back there amongst the red rocks, with that dry air blowing over me, the ringing in my ears of a silent, empty landscape. It is a fleeting feeling, and try as I might, I can never fall fully into it. Until I go back.

And so I found myself sitting in Denver International Airport, witnessing one of the most extreme displays of lightening I'd ever been privy to view. We'd just landed a short time before, clouds around my plane had been illuminated by the violent lighting in the thunderhead we had passed through (quite a rush, I might add). Normally,

I love thunderstorms, but I was in no mood for one at this time. It was nearing midnight and I was stranded in Denver; my flight for Las Vegas could not leave until the storm passed. Lighting silhouetted the distant Rockies, and I frantically texted my friend Alice "Road Runner" Hunt, who was patiently waiting for me at the Las Vegas Airport. Digital apologies flew hundreds of miles while I waited to leave. When I finally got to Las Vegas, it was after 1 AM and I was cracked out from too much coffee. But the excitement of seeing my old friend and the anticipation for our adventure perked me right up.

Alice and I go back a bit, to my freshman year at college (which college? I'll never tell). She's a scrappy sombitch, earnest, honest and completely loyal. Crass when she needs to be, but always good to have around. We lived in a dorm flooded with Latin-studying classics majors and budding archaeologists. Alice was somewhere between the two. I, on the other hand, was an ad kid with good connections and a Latin-filled youth, so I got to live in this beautiful brownstone in Boston. Alice and Tomek (

you might remember him), both older than me, took me under their wings and we became the three musketeers of the dorm. We were family. Over the next three years, we went on myriad adventures -- though none quite appropriate for this blog, so we'll start here. In Nevada. At 1 AM.

Alice, originally from the Midwest, had gone to work for several parks after graduating: Yosemite, Sierra and finally Death Valley. Being out west and all made it hard for her to come back East to visit Tomek and me, so we decided to head out to visit her. Besides, it'd be more fun to explore the Mojave than Boston's numerous swamps. The problem was Tomek pushed off buying his ticket until the prices soared above $500. So he was out and I went alone. It happens. The drive to the park was a bit of a blur. The land was dark and only a few stars managed to shine despite the ambient light of Las Vegas (no joke, you can see the lights of Vegas from Death Valley, over 100 miles away. It's atrocious, as is Las Vegas). We passed Pahrump, stopping for some supplies (it's the nearest place to the park to get anything), before continuing into the desert night.

Looming shadows of mountains passed on both sides. Ghostly sage brush and desert holly -- caked in dust -- were illuminated by our headlights. The bright green glow of a kit fox's eyes stared at us from up the road, before it darted off into the unknown. Our headlights reflected off of the white stucco wall of the Amargosa Opera House, a lonely hotel that stands in a ghost town on the border of the park. Alice pointed out sandy bluffs that indicated we'd passed into Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land (there are wild horses there, somewhere). We passed between two low mountains and I spotted a sign ahead:

Death Valley National Park

Homeland of the Timbisha Shoshone

We'd made it. By now it was 3 AM and fatigue was overtaking me. We pulled up to her apartment -- a cinder block building atop a hill, surrounded by tall, sandy bluffs -- and I fell into a deep sleep that would last for, oh, about four hours.

* * * *

In the morning we woke early, ate a hardy breakfast, and I got to meet Alice's boyfriend French Gilman, a delightful, friendly and fun young fella, with wild hair and a scraggly beard. Calm and cool, he's instantly likable and I spent my time there making sure I impressed him (which, being that I'm the long-time friend, isn't it supposed to be the other way around? Oh well, I liked the guy).

It was still early when we grabbed our packs, food and water and hopped in their white Izuzu Trooper. My first view of the Mojave from their front door was vast; if it hadn't been for a distant sand storm, one could see clear across the valley. The sky was a blinding blue and the air was dry, with that warm, sandy smell. The Mojave desert is quite different from the Sonoran. While the Sonoran is full of tall creosote bushes, towering Saguaro and countless prickly pear and cholla cacti, the Mojave is barren. Small bushes scatter the landscape -- a desert holly here, some sagebrush there. Where in the Sonoran, you can hear the rustling of lizards and quail, spot cactus wren darting between thickets, and spy some raptor cruising the thermals above, the Mojave is quiet, still. Almost hauntingly so.* On a distant road, a caravan glides across the empty landscape, silent and distorted by the heat reflecting off the ground.

|

| The road to Grotto Canyon. We were stuck here |

The park seems infinite. When you leave one valley, you just pass into another vast, empty wilderness. On the road, my eyes were glued to the window, watching the endless mountains pass us by. These were not the granite behemoths of my native land, but appeared like layers of packed mud that had erupted from the horizon in myriad chaotic angles -- which is exactly what they did. Not hidden beneath a blanket of flora, the mountains displayed the dynamic geological history of Death Valley; it's no wonder the area was once -- and still would be without the Department of the Interior -- a rather viable mining region. Ancient layers of mud, rock and detritus paint the mountains in a brilliant palette of browns. Green browns, red browns, blue browns, brown browns. Alice quipped that Death Valley had been referred to as "a study in the shades of brown."

We took a left off the main drag and followed a dirt road five miles into the bush. The road was on a steady incline as we neared the mountains and Alice informed me that we were on our way to Grotto Canyon to do a little light canyoneering. The smaller mountains ahead were a tan color, with those looming behind them rust brown, blood red and black. The smooth dirt road slowly became more sandy and our car struggled over some deeper pockets of loose dirt. When it seemed that we'd made it past the rough patches, the wheels of the car emitted a high-pitched whining. We'd become stuck in the sand. Alice took the wheel while French and I got out and pushed. It was no use -- the sand was so deep; even we were sinking into it. The wheels kicked up dirt, covering us in a thin layer of dust.

"Well," I shrugged. "Couldn't have gotten stuck in a purdier place."

|

| Entrance to Grotto Canyon |

I was surprised to learn that a car dubbed "Trooper" didn't have four-wheel drive; it seemed unAmerican. We would have to get out with just two-wheel drive and our wits.

We tried every trick we could think of. Floor mats under the tires. Digging out the tires. Pushing some more. We were five miles from the main road, exposed to the sun in a remote part of the park and the day was getting hotter. It was after ten and the heat was already in the 90's. We couldn't walk back to the main road without succumbing to the heat, our cell phones had no service, and Alice and French weren't too keen on using the satellite phone to call a ranger for help. The embarrassment would have been worse than death itself.

|

| French climbing up a dry fall |

We'd been working on the car for the better part of an hour when we came up with an idea. Digging through the trunk, Alice produced a car jack. We lifted the rear tires a few inches off the ground and filled the pits below the tires with large stones. Digging trenches in front of the tire tracks, we filled those with large rocks as well. Once we were satisfied with our makeshift cobblestone road (being from Boston, I'm kind of an expert on those), French hopped in the driver seat and gunned the Trooper while Alice and I pushed like our lives depended on it -- which they did. After a troubled start, the car made it out of the sandy patch and shot up the road. There was much rejoicing. Alice and French asked me if I still wanted to go on the hike or if I was too freaked out to carry on. I said I was good to go -- it's not an adventure unless you almost get stuck in the middle of nowhere, after all. We headed up the road and came to its nexus. Ahead was a sheer wall of rock with a gnarly opening in the middle: Grotto Canyon.

|

| Chuckwalla! |

We climbed through the winding canyon. Smooth rock slides, trenches and falls had been carved by a millennia of rushing water. Rocky overhangs gave us shade from the sun and the canyon was cool and breezy. Spires of sunlight poured through openings overhead. Here and there, we would come to big bends in the dried river where the canyon would open up. The sky was blue and cloudless above, and the heat radiated off the tall, sloping canyon walls. A chuckwalla --

my favorite lizard -- sat basking on a rock. This one was unlike those I'd seen in Arizona, however. It was black and a white-tan, with a leopard pattern and dark, black circles around its eyes. Before I could get too close, it darted under a rock and inflated itself in the crag. The trail brought us to many small, dried waterfalls and we had to shimmy ourselves up these narrow rock slides. Occasionally, we would come to a fall that was too high and broad to climb up, so we would launch French up and he would drop a line down to pull us up. After stopping for a small lunch, we came to a fall that was too great for any of us to ascend and we turned back.

|

| Pesky buzzworm |

Coming back down the waterfalls was much easier. Aside from the steep drops where we had to use rope to get down, we simply slid or jumped down, using the deep pool of sand at the bottom to brace the shock of our landing. We came to a bottleneck in the canyon, where the hard rock walls stood high above and close together, when Alice shouted my name and French grabbed my shoulder. They had seen it moments before I had unwittingly nearly stepped on it: A young sidewinder. El crotalo cornudo. It couldn't have been more than seven inches long, but that is when they are the most deadly. You see, most venomous snakes learn over their lifetime that they do not need to use their full supply of venom to incapacitate prey and predators. Small amounts will make the point. But the younger asps have yet to learn this. So if you are bit by a young viper, you are more likely to die. Most of the folks I've known from the Southwest are very keen at spotting snakes -- more so even than me, a person who loves all things herpetological. I was very lucky these two had picked up this trait. The sidewinder coiled itself tight, ready to strike, with its small rattle shaking furiously. The rattle itself was so small that, even a foot away, I could not hear it. Like I said, I was very lucky Alice and French stopped me. We gave the snake some space and watched it slither off -- to where? I don't know, there was a waterfall up ahead that it would be unable to summit. Oh well, not my problem.

.JPG) |

| A mountain lamb! Photo Cred: Alice |

Coming back to the opening where I'd spotted the chuckwalla, I was no doubt telling some long story at an obnoxious volume, when I rounded the corner and spotted six bighorn sheep standing right in front of me.

"Whoa! Fuck!" I shouted, causing them all to pause and stare at me before darting up the steep slope to our right.

|

| Grotto Canyon Skylight |

They hadn't heard us coming -- strange, because I am not known for speaking quietly -- and were caught quite by surprise when we came around the bend. The slope they'd hopped up grew too steep for them to climb any further, so they stood where they were and watched us pass, giving us a wonderful opportunity to view them. There were two adult females, two juveniles and two lambs. We all stared at each other silently for a time before our group moved on, giving them the opportunity to run and hide deep in the winding canyons.

* * * *

|

| Mesquite Dunes |

It was late afternoon when we made it back to the car, and we gunned the Trooper down the sandy road so we would not get stuck again. We took a short reprieve at the expansive Mesquite Dunes, where I took off my shoes and socks and let my feet sink into the sand.

French and Alice took me out of the park to a podunk old mining town in Nevada called Beatty. It's a rough little desert community, a little run down, but quaint and welcoming. Western-style buildings, stucco houses, trailers and cinder block garages stand beneath cottonwood trees. The mountains were casting long shadows when we parked the car.

|

| Happiest Place on Earth |

We walked to the

Happy Burro Chili & Beer and sat down around an old wood spool on the side porch, beneath a canopy of Christmas lights. The building itself was little more than a shed, but it had beer so I wasn't going anywhere. The bartender came out to greet French and Alice and ask me for my ID. I presented it and she asked how old I was. I wasn't prepared for an interogation, so my brain managed to fire off "It's July 4, 19XX so I am 23 years old." Completely unsuspicious. French brought out a pitcher of the coldest PBR I've had the pleasure of drinking -- the pitcher had a frozen gel pack in the middle that kept the beer cold in the Nevada heat. Drinking from mason jars, we were delighted when three bowls of chili came out. I am here to tell you, hand to my heart, that it was the best damn chili I have ever had, will ever have. Big beans, chunks of steak, and delightful ground beef filled my small bowl. It took great self control for me to not suck the whole thing down immediately; every bite needed to be savored, like I'd never relish in its goodness again.

|

There was no time to take a photo

of a full bowl |

We enjoyed some more pitchers of Pabst while engaging with the local color. An old coot, sporting a false visor hat with fake hair on the lid, called Uncle John, came and chatted us up a bit, asking Alice when she would leave French to marry him. A dog named Hooker sat on a stool at the bar and came over occasionally to see if I would give him some of my chili. I was told the canine was the true owner of the bar -- indeed, a sign inside reads "Hooker runs this bar" -- but it didn't help him get any of my coveted chili. A younger couple, about our age, sat down next to us and the young woman quietly ordered a glass of white wine. It took a great amount of effort for me to not turn around and stare at her. Yeah, I thought. They'll go bust out their vintage Carlo Rossi for you. A man in a long, black duster and cowboy hat appeared at the entrance and sat at an empty table -- he looked like he was straight out of Tombstone. The Cimarron Kid. Alice and French warned me not to interact with him/look at him; he was a mean drunk with a quick temper. And he was armed. Two six shooters and a big knife. Finishing our beers, we brought the empty pitchers and glasses inside, paid our tab -- no joke, less than $20 -- and headed out. The gunslinger peered at me from under his black Stetson hat, his cold, sunken eyes surveying us as we left.

Back in the park, Alice took a sharp right off the main road. I was confused, as I knew we weren't back at their place yet. They told me they had something cool to show me. It was pitch black as we drove up a dirt road, unable to see far ahead. The ghostly visage of an abandoned building stood on the side of the road, a sign in front indicating that it was -- at one point -- a bank. They'd taken me to one of the area's numerous ghost towns: Rhyolite. Passing several gutted, dilapidated buildings, we came to the top of the road, where a grand old train station stood, surrounded by tall Joshua trees. We couldn't get too close, as there was a fence surrounding the building, but we admired the lovely Turn of the Century architecture. Walking past a an open mine shaft in the ground, French peered in and jumped back just in time to dodge a bat that shot out from the abyss. We wandered for a bit more before French and Alice said we needed to head back home. We had a long day ahead of us.

Continued soon in Part II.

*This is certainly not to say the Mojave is devoid of life. On the contrary, Death Valley is home to a plethora of unique and wonderful plants and animals. This needs to be noted so Alice and French don't chew me out next time I see them.

Rory's note: Yeah, the names in this are very much nom guerras.

.JPG)